- Home

- Clare Strahan

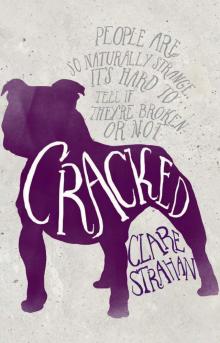

Cracked

Cracked Read online

This project has been assisted by the Australian Government through the Australia Council, its arts funding and advisory body.

First published in 2014

Copyright © Clare Strahan 2014

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system, without prior permission in writing from the publisher. The Australian Copyright Act 1968 (the Act) allows a maximum of one chapter or ten per cent of this book, whichever is the greater, to be photocopied by any educational institution for its educational purposes provided that the educational institution (or body that administers it) has given a remuneration notice to the Copyright Agency (Australia) under the Act.

Allen & Unwin

83 Alexander Street

Crows Nest NSW 2065

Australia

Phone: (61 2) 8425 0100

Email: [email protected]

Web: www.allenandunwin.com

A Cataloguing-in-Publication entry is available from

the National Library of Australia

www.trove.nla.gov.au

ISBN 978 1 74331 603 0

eISBN 978 1 74343 464 2

Cover & text design by Astred Hicks, Design Cherry

Typeset by Midland Typesetters, Australia

Anthe, remember how you spoke the chorus of Leonard Cohen’s Anthem to me and inspired the first line of a novel? Well – here it is.

I’ll ring the bells,

my darling friend.

Anthea Joy Simpson

1972–2013

CONTENTS

ONE

TWO

THREE

FOUR

FIVE

SIX

SEVEN

EIGHT

NINE

TEN

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

I cracked when I was eleven, but it didn’t show. People are so naturally strange, it’s hard to tell if they’re broken or not, but I’m pretty sure that by the time I finish high school, I’ll be a pile of shards, beyond repair.

Over the crest, there it is, Fernwood Secondary College and the continuing joys of Year Ten. Every day is like being submerged in its semolina sand.

Imagine just rocking up, full of gossip, not caring about anything but the latest YouTube. Saying ‘Hi’ and sitting at my desk exactly as if I belonged. Yeah, that’s what I’ll do.

No I won’t.

For one, my mother hates Facebook (where all good gossip breeds) and refuses to let me on it. And for two, life turns darker and bleaker the closer to school I get.

I don’t know why. Maybe it’s a pathological condition I’ve inherited from my father – along with the weird mole on my left shoulder blade?

I have no way of telling.

By the time I’ve been to the office for my late pass and am shuffling down the nearly empty corridors to Mrs Sutcliff’s Australian History class, I won’t look anyone in the eye. Mrs Sutcliff is setting up the TV trolley when I arrive; which doesn’t work because someone who ‘didn’t know what they were doing’ – aka Sutcliff – has pressed the wrong buttons or plugged in the wrong cable.

I’m hungry. I haven’t had breakfast. I blame Shakespeare.

Every year my mother directs an amateur Shakespeare production, usually A Midsummer Night’s Dream. I used to love it and the oldies have fun, but now it’s annoying: after being on organisational overload for everyone else, racing around like a maniac doing a million weird theatrey things and the high of the closing night, at home Mum’s a zombie, a deflated balloon; empty: like our fridge. And chaotic, like the rest of the place: jumbled with bits of set and great disorganised bags of costumes, and ‘cloths’ . . . loads of cloths. But no bananas. No bread. No milk.

‘Gods, it’s Monday,’ Mum said when she shook me awake this morning. ‘And you’re late.’

When she rushed me out the door she stuffed a few Greek shortbreads – a gift from our neighbour – in my lunch box and scrabbled in her wallet for gold coins. ‘I hate to surrender to the culture of prepackaged dispose-a-food,’ she said. ‘But you’ll have to buy lunch.’

Sutcliff abandons the DVD and drones on instead about the riveting details of the Australian parliamentary system. All I can think about is Greek shortbreads. Sutcliff’s voice sharpens up to say, ‘Clover Jones, put that lunch box away.’

Sutcliff has never liked me. She’s always ringing my mother to tell her I’m disobedient and insulting.

My mother, the walking dictionary, with her 1930s fashion and pearls. Until I left primary school, I hadn’t realised what little clue Mum had about real life. She’d wanted to send me to the Steiner school where I went for kindergarten, but we couldn’t afford it and she never got over the disappointment, crying into her pillow at night. At least, I thought that’s what she cried about.

She made up for it with her photograph album of my ‘stages of development thus far’, shared so teachers can get a picture of me as ‘a whole person’, ‘an evolving spiritual being incarnated into a physical body who needs nurture and compassion’; her long letters urging change and the virtues of establishing a ‘Steiner-stream’ in the state school system; her offers of candles and storytelling. Once, she wrote to the school complaining that Sutcliff had ‘undermined my self-esteem and displayed a concerning lack of judgement’.

‘Mum, you didn’t?’

‘Clover, I did.’

‘Now she’ll really hate me.’

‘No she won’t.’

But she does. If she could burn a hole in me right now with the glint from her glasses, she would.

‘Well, Clover?’

People stare. My stomach grumbles, loudly, like an alien percussion instrument played underwater. Sparks of amusement flicker around the room and the flames creep up my neck.

Rob Marcello cracks his knuckles and says, ‘Gross.’

Everyone laughs, even Alison Larder, my red-faced and strange ex-best friend.

Thuggish Pete Tsaparis reaches over to slap Rob on the back. ‘Gross, all right, Robbo.’

Rosemary Daniels and her friends smirk behind their make-up.

Sutcliff half-quells them with her hand. ‘Clover, is there something you’d like to say to me about this disruption?’

‘Fuck off.’ That’s what I’d like to say.

What I’ve said.

Silence strikes like lightning. Trung Nguyên drops his pencil case and someone makes the snorting sound of suppressed hysteria. Sutcliff thunders towards me so fast I nearly fall off my tilted chair.

‘Up,’ she hisses and marches me to the hard vinyl bench outside the principal’s office, disappearing briefly inside and then striding off without a backward glance.

Sitting next to me, watching with some interest, is Philip McKenzie.

I haven’t been this close to Philip since we had to sit next to each other once for punishment at primary school, and we’ve hardly spoken since the first day of high school. Mum had insisted on seeing me off at the school gate that first day and she’d cried so hard it was impossible to understand her, but it had sounded like ‘I’m sorry.’

‘Go home, Mum. I’ll be fine.’

She’d straightened her back, blown her nose and walked off, looking brave, our black staffy, Lucille, trotting unconcerned beside her.

Philip had smirked at me and said, ‘Your mother’s a freak.’

‘Yeah?’

But really, I had nothing to say to that.

He looks different. Sort of. He’s tall and skinny now and has a few pimples on his neck. He must be fifteen, too. But his face is as smooth-skinned as ever, with its sprinkling of freckles. His rust-co

loured eyelashes. His blue eyes, mocking.

Grade Six looms in my mind’s eye. Our teacher, Mr Henderson, telling us about his ‘maths heroes’ and passing around a photo of Albert Einstein. Alison thought Einstein was famous for creating the ultimate wacky-professor hairdo, but apparently he’d worked out some theory as well, the significance of which Mr Henderson was trying to impress upon us at the same moment that a mighty spit-ball hit Philip McKenzie in the head. Mr Henderson glared. ‘It’s no laughing matter,’ he said. ‘The Americans took Einstein’s theory and turned it into the atomic bomb. A nuclear weapon that even today can destroy the world. Boom! Just like that.’

His eyes swept out the window – Mr Henderson liked to look out the window when he talked; the distraction of our actual class sitting in the actual room seemed to disturb him – and told us all about it. The A-bomb, tick-ticking away out there, waiting for the right crazy general to press the button and set off a chain reaction that could blow everything to smithereens and leave whatever was left so poisonous it would kill for thousands of years. ‘The upside is that these days nuclear power plants are in operation all over the world, making electricity using uranium, and uranium is one of Australia’s natural resources.’

‘But isn’t nuclear electricity radioactive?’ I blurted.

Half the class sniggered, and Philip McKenzie flicked a rubber band at me.

‘Stupid,’ he said.

Mr Henderson jerked around irritably. ‘Phil, we do not throw things at each other in class. Apologise to Clover.’

‘Sorry, Clover-bomb.’

I managed to score a direct hit with Philip’s rubber band on the side of his curly red head. Mr Henderson spun around again, but Alison Larder saved me with her urgency.

‘How do we get rid of it?’ she said.

‘We can’t. Nuclear weapons, once they’re made, can’t be . . . unmade.’ Mr Henderson blushed. His words had left a silence.

Alison broke it. ‘Is it just one bomb? Couldn’t we get it? Couldn’t we hide it, I mean? I mean, my dad’s got a huge garage. How big can it be, one bomb?’

‘Oh, no.’ Mr Henderson shook his head as though he pitied us immensely and wiped his glasses. ‘They called the first nuclear bomb “the A-bomb”, Alison, but there are hundreds of nuclear weapons nowadays. Thousands. Bombs and missiles and torpedoes. Enough to destroy the planet many times over.’ He rubbed the kidney bean shaped marks on either side of his nose and put his glasses back on. ‘What with climate change and whatnot, reducing nuclear arms is not considered the most pressing issue these days.’

And that’s when it happened. The crack. I felt it, deeper than my bones. They’d made a bomb that could destroy the world. Okay, I could handle a mistake. But then they made thousands of them? And now it wasn’t even the most pressing issue. Did that mean everything else was so bad that the world might not survive long enough to blow up? We stared at Mr Henderson like desperate rabbits. Well, that was how I’d felt; trapped in the headlights of imminent destruction, small and twitchy with front teeth a little large for my head.

Mr Henderson looked sweaty, I remember. Maybe he’d just noticed our pale faces and feared he’d gone too far, worried what our parents might say. Mine, for one, was likely to complain. Lucky for him, the bell rang.

Philip shoved past me, hissing in my ear. ‘That’s not really the bell, it’s an alarm. They’ve launched a Clover-bomb at Fernwood Primary School.’

I laughed in a jeery way and it felt better than crying, but aftershocks were pounding me on the insides and Philip McKenzie was right: I thought I might explode.

After school that day, Philip stopped opposite me, sitting on his stupid bike in the schoolyard making a fake siren sound.

‘Ranga,’ I said. Pretty weak, but Alison Larder backed me up, smirking.

Philip was immune. Growing up with clown hair had made him impervious to the insults of amateurs. He just rode one-handed, twirling his finger as if to say ‘big deal’.

‘Is my hair red?’ Philip rode his bike so close, he practically ran over my toes. He was great on that bike and I couldn’t ride at all. I shuffled back and stood on Alison, who said, ‘Ow.’

Turning impossibly, Philip rode back the other way, circling us. ‘Gee – a ranga. I hadn’t noticed that, Clover-bomb. You’re so clever to point that out. Thank you. You’re so kind.’

Like a ginger cat snaking off, he’d gone, leaving a little puff of disdain.

In true me style, I’d run home.

Mum was gardening. She seemed small and alone and frail, holding up a lopsided dirt-covered onion. Did she even know we were all going to die?

‘Well,’ she said. ‘What do you think of my onion?’

‘I hate your stupid onion!’ And I dashed inside. Lucille ran in with me, barking.

Mum gathered us up – Lucille, onion and me – to sit on the couch. She brushed the dirt off and laid her treasure, papery and golden, in my palm. ‘What’s up?’

I remember my hand curling around the onion. It was a good one, fat, still smelling of earth. Earth. How could the whole earth be destroyed? Were we going to boil to death? Would the seas rise up and sink us? I couldn’t find the words to ask, and was afraid of the answers. But Mum wasn’t one for letting tears go by without explanation.

In the end, because I didn’t know how to explain everything Mr Henderson had said, I blurted, ‘Philip McKenzie reckons I’m stupid.’

And sitting here now outside the principal’s office, I guess he probably still does. He jiggles his leg and I can feel the vibration through the bench.

The leg stops and he says, ‘What d’ya do?’

‘Swore at Sutcliff.’

‘Yeah? Didn’t think you had it in you . . . Clover-bomb.’ The old name buzzes through me, but his low-key approval flicks a switch and I breathe out; maybe it isn’t a nuclear disaster after all.

The clock on the wall opposite us ticks. Loudly. Philip cracks his knuckles. ‘So,’ he says. ‘What happened to you and Alison Larder?’

Why do I feel like crying? I’ve barely had anything to do with Alison since we started high school and feel embarrassed about half the things we did when we were little.

All through primary school, Alison Larder practically lived at my house. Our favourite thing was laughing. We had this theory that laughter shook the black stuff off your soul. All it took was a certain look from Al and I was hopeless, helpless. We literally fell about: nothing could stop us but exhaustion. And we were always making cubbies, in the lounge under Mum’s theatre cloths pegged on string, or in the garden, or up the Golden Ash. And everywhere we went, Lucille came too. Wherever we played, we drew. Especially me. I loved drawing. Sometimes when Alison got sick of it, she’d make up stories (they usually had Jesus in them, but I didn’t mind) and I’d draw the pictures and we’d make little books for my mum.

‘Well, well,’ she’d say. ‘Jesus and the Snails, how lovely.’ Or whatever crazy tale it was.

Sometimes we went to Al’s, but not often.

The first time I went she whispered, ‘You can’t put your feet on the seat.’

‘But I’m only wearing socks?’

She nodded seriously. ‘Even socks can make a mess.’

I reckon Alison’s mum would rather have died than let Al climb a tree or have a dog sleep in her bed under the covers. Especially one as smelly as Lucille.

Everything we did at my house made a mess: wet-on-wet watercolour painting; clay modelling; and, when we were very little, ‘soapy cooking’ with tiny kitchen utensils and grated yellow soap mixed with mud. Al was always wearing my clothes and getting them filthy. Before we went to bed, Mum ran bubble baths that smelled like lavender.

I think Alison loved my mum more than I did.

At the end of Grade Six, just before the school holidays, the longest school holidays that ever were, Alison’s dad got some special position in a church in Canberra and her whole family moved away.

‘Mum wants to be there

for Christmas. Settled in by Christmas,’ Al told me, sobbing with the horror of it.

‘You could live with us. My mum’ll adopt you,’ I said.

Alison looked hopeful. ‘Maybe my mum will let me bring one of our TVs?’

‘And if Mum doesn’t like it, we can live in the tree.’

‘What about electricity?’ Al gazed knowingly at the house. ‘I guess we could use an extension cord. Dad’s got a really long orange one that’s allowed to go outside.’

What would I do without her? I couldn’t even climb the tree on my own – one of us had to give the other a bump-up and then the person up the tree had to hook her legs over one branch and feet under another branch and hang half-upside-down to help the other one get up.

I reached down and hoicked her up. ‘I’ll never have another friend as smart as you, Alison.’

She scrambled for a foothold and then practically ran up the trunk, like a monkey. ‘I’ll never have another friend with hair as long as you, Clover.’

‘You have to stay here. My mum won’t mind.’

‘We’ll be like sisters,’ she said.

I felt a stab of jealousy in case Mum loved her more than me, but said, ‘We’ll be like real sisters.’

‘Sisters forever.’

‘Sisters until we die.’

Alison said wickedly, ‘Sisters until Philip McKenzie dies.’ And we laughed until we had to hold on to the tree to stop ourselves from falling out. Then sat in the broad branches and didn’t say much until Mum called us in to wash our hands for dinner.

It didn’t matter how we cried and hated our parents; they wouldn’t agree to our plan. Alison moved away and I headed to high school.

Fernwood Secondary College drew kids from a few surrounding primary schools and lots of them had been at my school, but I felt like I hardly knew anyone. I blamed Al for my complete lack of ability to make new friends.

On that first day Mum said, ‘Just be yourself, love. You’ll be fine. You’re wonderful.’

Be myself? My wonderful self?

Cracked

Cracked