- Home

- Clare Strahan

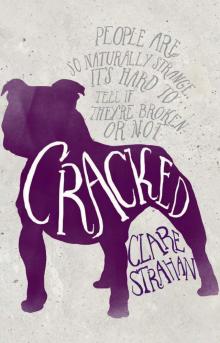

Cracked Page 13

Cracked Read online

Page 13

She dumps the DVDs, fossicking around where she keeps her purse. ‘I have no idea what I’ve done with that money, but it was food or movies and I got movies. It will have to be left-overs after all. But I managed the orange juice. Hey! You’re not crying over pizza are you? You should be thinking yourself lucky you’re not on bread and water.’

I hug her. ‘I love you,’ I say.

‘I love you, too.’ She kisses the top of my head. ‘But for God’s sake, Clover – behave yourself, okay?’

Heading to school on Monday morning, I still feel queasy, but I’m not game to ask Mum for the day off. I figure all I have to do to avoid Keek is hang out with the Herbs. They have their own circle of logs down the back and I am all set to ignore him, but he doesn’t turn up.

We stroll to the quadrangle. Keek calls it ‘Herb Headquarters’ and avoids it like the plague. Two close shaves have convinced me I’d better stop thinking of them by their herb names.

Rob bounces up to me, full of beans. ‘Hey,’ he says accusingly. ‘We went off the other night to get beers and when we got back, you’d gone.’

‘Is that what you went for? Beers?’

He tickles my ribs and jiggles his eyebrows. ‘What else?’

I don’t reply. Rob’s beautiful, grinning face begs to be kissed, if I had the guts. What if Pars— Natalie has it all wrong?

‘So where’d you go?’ he asks. ‘I thought you were crashing at Rosie’s?’

In the distance, Keek zooms in on his bike. I watch him chain it to the bike rack. Cho bounds over to him across the asphalt and they speak for a minute. Seeing them together, I realise he’s tall. As tall as Robbo, probably, but a third of his width. Then she hugs him. I can hardly believe it when he lifts his dangling arms and puts them around her. They just stand there.

‘Hello?’ Rob knocks gently on my head. ‘Anyone at home?’

‘Sorry.’

‘What is it with you and good old Phil, anyway?’

‘Nothing.’

Rob is sceptical.

‘We’ve known each other since primary school, but now his parents don’t want him to have anything to do with me.’

‘Bad vandal-girl. And he cares what his parents think?’

‘His mother’s – not well.’

‘Well, the little BMX Bandit’s loss is Captain Robbo’s gain. I want you to go to Josh Eldrich’s with me on Saturday night. That’ll be a real party.’

A giant Fruit Tingle is melting in every part of my body. I can hardly breathe. The footy crowd is moving off and calling for Rob to go. Another party so soon after my last effort? And at Josh Eldrich’s, who doesn’t even live with his parents? But I can’t quell the Fruit Tingle and the pressure makes me want to scream.

‘I don’t think my mum will let me,’ I manage, against my will.

‘C’mon, Jones. It’s finals. Come down and watch me play Saturday and we’ll go from there. Then we’ll send her a text message. I gotta go.’

‘She doesn’t have a mobile phone.’

He’s running towards the oval but flashes me a grin. ‘Even better!’ he calls. ‘She won’t know where we are.’

Rosemary scoops me up to sit with her on a bench, pushing off the three kids already there. They leave without even complaining. ‘You gonna go?’ she says.

‘There’s no way my mum will let me.’

‘Well I reckon you better go.’

‘Why?’

‘Katie told me she’s going.’

Sage! ‘So?’

‘They hooked up after you left. Katie and Robbo. Practically did it in Josh’s ute, but Katie had her rags. That’s what Ellen told me, anyway.’

‘Maybe he should take Katie then.’

‘But he didn’t ask Katie. He asked you. And you know Ellen. She’s jealous as hell when it comes to Robbo. She could’ve made it up.’

‘Why are you telling me then?’

Rosemary shrugs. ‘You’re so weird, no wonder your name’s Clover. C’mon, it’s maths time.’

How am I supposed to think about maths? Mr Ratshit’s ear hairs make me vomitus. And where has Keek disappeared to? He’s supposed to be in maths. I’d forgotten all about him because of Robbo and Katie and bloody Ellen and don’t know if he’s gone off with Cho or what.

‘. . . Clover?’ says Radshaw.

‘What?’

‘Why are you not writing down the problems?’ Mr Radshaw is looking at me as though I’m supposed to know what the hell he’s talking about.

‘What problems?’ The fracture opens and spews out lava in triangles. ‘What do I need more problems for? Why are you loading us up with problems? Who gives a shit about the size of triangles? What the hell difference does it make, Mr Radshaw? The world’s going down the toilet and you can’t trust anyone.’

‘You can’t swear at me like that. It’s not on.’

‘Jesus, Mr Radshaw, is that all you’ve got to offer? Pythagoras was a philosopher for God’s sake. He changed the world – why don’t you stand up for his bloody triangles?’

‘Sit down and write the homework equations. If you don’t, you’ll be staying in after school until it’s done.’

‘Fuck off,’ I say.

Rob comes to see me while I’m waiting on the vinyl bench for Mum. Keek still hasn’t shown up.

‘I hate Berty,’ I say, under my breath.

Rob yawns. ‘Do the crime, you do the time.’

‘Ratshit’s an idiot.’

‘So what? Just get on with it. That’s what I reckon.’

‘I’m suspended again.’

‘I heard. How long?’

‘A week.’

‘A week?’ He lowers his voice. ‘What did you do?

Tell Berty to fuck off, too?’

I snap off a thread hanging from the hem of my school uniform, modified by Rosemary and short as any Herb’s.

‘Jesus, Jones. What’s your problem?’

‘School.’ My voice is all croaky with tears. ‘School is my problem.’

Rob shakes his head. ‘I don’t get it: it’s just school.’ He stretches. ‘Well, I guess I’ll see you at the game then, on Saturday?’

‘Will Katie be there?’

‘Katie? Maybe. Why?’

‘I thought you two were . . . you know.’

‘What makes you think that?’

But my courage fails me. I sniff and tug on my skirt – it really is too short.

‘Jealous? That’s a good sign.’

‘Is it?’

At the appearance of a couple of mates, Rob is off again, up the corridor. ‘Means you want me, Jones,’ he calls. ‘You want me bad.’ He disappears in a rowdy knot of sniggering testosterone and is replaced by Ellen, hurrying along the corridor out of breath.

‘I wanted to catch you before you left,’ she pants. ‘Did you know that Philip McKenzie is going out with Cho?’

Three nights into my suspension, Aunty Jean arrives on the doorstep after nine, unannounced. Months ago my mother agreed to go with her to Queensland for the weekend, but she’s cancelled because of ‘everything that’s going on’ and Jean’s here to insist Mum ‘honour her commitment’. I’m packed off to bed as soon as possible, but creep back up the hall, listening through the partially open door.

‘Come on, Pen. Clover will be all right. She’ll be with Mrs Tzatziki next door and she can always invite her sexy little side-Keek to come and keep her company.’

‘Jean!’

‘What? The kid’s cute, what can I say?’

‘You’re shocking.’

‘No, I am not. You’ve just lost all sense of perspective. Relax, you know perfectly well that I’m not interested in premature ejaculators – but he’s a little hottie, Penelope, like his dad. Anyway, are you coming?’

‘I don’t know if it’s fair on Yiayia, she’s getting old. And Clover’s been arrested, Jean. And now she’s suspended from school again.’

‘See? She’s killing you. You need a break.’

<

br /> ‘I don’t think it’s the right time—’

‘It’s nearly seventeen years since “the right time”. This is bullshit. You just don’t want to spend time with me. With yourself.’

‘Don’t say that, Jeannie.’

‘Well? Come! I know it’s cheesy Gold Coast corporate nonsense, but who cares? It’s all paid for and there’s massage . . . and karaoke . . .’

‘Karaoke?’

‘Okay, fair enough. But come on, Henny Penny. Massage. Beach. No dickhead Dave. Free food. No bills . . . and it’s a fabulously kitsch Surfers Paradise hotel by the looks. And it’s been booked for months.’

‘I’ve got nothing to wear.’

‘I’ve got clothes enough for both of us.’

‘It would be fun to get away.’

‘Mrs T can cope with Clover for one weekend, surely?’

‘I suppose it might even be good for her.’

‘That’s it Penny: do it for Clove. God forbid you do it for yourself.’

‘Stop making me out to be a masochist.’

‘It’s your fault.’

‘It’s my fault that you’re making me out to be a masochist?’

‘No, I mean Clover.’

‘What do you mean?’

‘She’s a chip off the old block, that’s what I mean. You were an angst-ridden drama queen always telling teachers to stick it up their jumpers.’

‘I was not.’

‘Mr Farquharson?’

‘Well, the man was practically a fascist – what kind of subject is consumer economics? Brainwashing into the same neoliberal values that are currently wrecking the planet. Cooperating with him would have been tantamount to appeasement.’

‘What about Mrs Thompson? All she did was try to get you to run, you lazy little cow.’

‘Shut up, you.’

‘Poor woman. She had a nervous breakdown in the end.’

‘That wasn’t completely my fault.’

‘It was a group effort, true, but still: she probably still has nightmares about you.’

Mum scares the crap out of me by getting up to shut the door. ‘Shh. She’s enough trouble as it is without—’

But I’m gone, back to bed, half-thrilled and half-terrified at the idea of maybe being able to talk Yiayia into letting me go to Josh’s party after all, and totally pissed off with Mum and Aunty Jean for talking about me behind my back.

Mum gives me the third degree while I sit on the bed and she packs to go away. ‘Do you swear on your grandparents’ graves that you won’t do anything to upset Yiayia while I’m away?’

‘Like, what?’

‘Like run around spray-painting the neighbourhood.’ ‘I swear it.’

‘Lucille’s grave.’

‘Mum.’

‘Swear.’

‘I swear.’

‘Have you seen Keek?’

‘No.’

Mum tuts and picks fluff off the cardigan she’s folding into the suitcase. ‘He probably doesn’t want to upset his mother.’

‘Or his girlfriend.’

She turns to me. ‘Keek has a girlfriend?’

‘Apparently.’

Mum’s packing slows and becomes careful. ‘Who?’

‘Cho.’

‘The one that beat him in that bike comp thing?’

‘Yes, the one that beat him in that bike comp thing. She’s liked him for ages.’

‘And he likes her?’

‘Apparently.’

She sits next to me, clutching a pair of socks. ‘How do you feel about that?’

I could fall into her lap and cry my head off, but I’m still mad with her for bagging me to Aunty Jean. ‘I don’t care,’ I say.

‘Well, you’ve had him all to yourself . . .’

‘I don’t care, Mum. Good for him. His parents hate me anyway and he’s obviously decided they’re right about me so good luck to him.’ I push away her comforting arm. ‘Don’t.’

Mum purses her lips and returns to her packing.

‘She’s an even bigger and more boring bike-head than him, anyway,’ I say.

Mum nods unconvincingly. She seems sad. Why won’t she believe me? Why should I care what Keek does? He’s not my boyfriend.

In a rush of fury I want to slap the worried, knowing look from her face. ‘I said I don’t care, all right?’ I yell, and leave. Or, as Mum describes it later when she’s ‘having a talk’ with me about my attitude: flounce out of the room.

On Friday afternoon Aunty Jean arrives to pick Mum up and it’s as though they’ve already stepped into another realm where I don’t exist, talking over the top of each other and joking about having sex with strangers. I hover between not being able to wait to get rid of them and latching on to my mother like a monkey, never to let go. When she finally leaves, half-dragged away by Aunty Jean, it’s a shock.

Mrs T is babysitting in Oakleigh until half-past eleven. A sense of freedom thrills through me. I bring the portable CD player from my bedroom, plug in the iPod and crank up my music.

Free, at last!

But when it gets dark, the creeps scuttle up my spine to the base of my neck and nestle there, freaking me out. I have to go to the toilet, but the hall is full of shadowed doorways.

‘Is there anyone there?’

Nothing.

The silence gets louder. Someone or something is watching me. Waiting. I take a few steps into the hall. ‘Lucille?’

A shadow looms. I scream.

‘Bloody hell, dog, are you trying to kill me?’ I grab her collar and make her go with me. It isn’t far, but as soon as the first doorway is behind me, I have to run the rest of the way because something absolutely is going to grab me from behind.

Rushing Lucille back to the lounge, I pick up the phone to call Keek – but don’t dial. He’s Cho’s boyfriend. His parents hate me. It’s impossible. Half my heart’s been chopped away. I slide down the wall and cry. The dog settles against me with a sigh.

There’s only so long one can sob on the carpet. I pull myself up, turn on more lights and try to make Lucille snuggle with me on the couch, but she keeps jumping off and going into Mum’s room. No doubt because, on account of her general hairy smelliness, I’m usually shoving her off the couch. In the end, I leave the TV on, crank up the music and get out my pencils. Drawing helps the creeps to slink off back into the night, until Lucille comes out to bug me with her extremely bad breath and full bladder and makes me take her outside, where they come scuttling back. I’m almost relieved when Mrs T arrives and makes me turn off the stereo.

‘You make your ears deaf as posts,’ she says, wagging a finger. ‘Bad as your mother with that Von Zeppelin rubbish of hers.’

Even though she’s making me mental, I take hold of her fingers and kiss her hand. ‘That was not Von Zeppelin, Yiayia.’ I’ve loved her hands ever since I was little; worn and weathered and brown with slightly paler palms. She works in the garden, but her nails are always whitish and clean. ‘I want to paint your hands one day, Mrs Theopopolous.’

‘Darling, you’re going to be a great artist.’

‘Thanks. Can I paint your hands?’

‘Of course. But do I have to sit still for long times? I don’t think I’ll be fun at that, Clover.’

‘I’ll take a photo.’

‘Okay, Michelangelo.’ She laughs, her enormous bosom rocking. ‘Come on.’

I haven’t slept over at Yiayia’s for years. She still makes the bed with crispy sheets and woollen blankets, her palm so firm on my forehead while she says a prayer over me in Greek.

Saturday morning at the Theopopolous’s has always been about food, but the spread on the kitchen table is daunting. ‘Is the family coming over?’ I ask, hopefully.

‘No, no, just us. Why?’

I’m saved from having to answer by the telephone. I’d forgotten that Mrs T yells into the receiver, as if the person is in the other room, or on another planet.

‘No!’ she shouts, and almost dan

ces on the spot. ‘Of course, I come immediately!’

She hangs up and rushes around the kitchen.

‘Is everything all right?’

‘No. Yes. My Olivia, her baby is coming early. I have to go.’ Her hand flies to her forehead. ‘Ach!’

‘What’s wrong?’

‘I fly to Sydney!’

‘Don’t worry about me. I’ll call my friend . . .’ I cast about for a name she won’t think is trouble. ‘. . . Alison Larder, and stay at her house.’

‘You sure?’

‘Yes. She’s always asking me. Quick, I’ll help you pack. Do you have to book?’

‘Theo, he all arranged.’

When the taxi arrives, she hugs me tight and hands me a slip of paper with numbers in her fine scrawl. ‘I can’t wait any more. You sure it’s all right for Mrs Larder?’

‘Yeah, I’m sure. I’ll get her to call Mum, anyway, so you don’t have to worry.’

‘Okay. Well, here’s Theo, his mobile phone. He’s not far. He says he will be our back-up man. Or you can go to his place now. What do you think?’

I think my brain is going to burst out of my heart because the universe clearly wants me to go out with Rob Marcello. ‘Alison’s will be fine, I’m sure of it,’ I say reassuringly, glad she’s handing her bag to the taxi driver and not looking at me. ‘Give my love to Olivia and say hello to Stephanie for me. I’ll call you if I need you. Thanks, Yiayia. Have a safe trip.’

Mrs T settles herself into the passenger seat. ‘Be a good girl!’ she calls as the taxi pulls away, and the bright, nervous, hopeful kiss she blows me makes me want to cry.

I feel like a criminal, heading home after waving her off, but it’s time to take Rob up on his offer. I haven’t seen or heard from him all week, so I can only assume I’m still invited.

But I feel like a complete knob when it comes to fronting up at the oval so I turn off and walk down to the bowl instead, then end up halfway to nowhere. I sit on a rock and have a smoke, courtesy of the emergency money Mum left me. Trung works part-time at his parents’ run-down milk bar and he sold them to me without even raising a fine black eyebrow.

Cracked

Cracked