- Home

- Clare Strahan

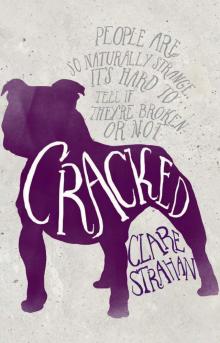

Cracked Page 4

Cracked Read online

Page 4

‘Is that really your dad?’ Steph had asked, seeming more bewildered than impressed.

‘Yeah,’ I’d lied. ‘That’s my dad.’

‘Led Zeppelin’s so ancient,’ I accused Mum and Aunty Jean, as soon as I got old enough to realise. I was secretly glad, then, that Mrs T’s married daughter had moved away to Sydney taking Stephanie with her, even though Yiayia had cried for a week.

‘They were already old when we were your age,’ Aunty Jean dismissed me. ‘Who cares? Monster riff!’ and they were off.

Aunty Jean doesn’t have children and is always asking Mum to go overseas. ‘For God’s sake, Penny, you’ll be a dried up old bag before long. It’s only six weeks!’ Mum always says no because of me. And because money isn’t what you’d call plentiful. But Jean’s all right. She makes Mum laugh and buys me clothes so I don’t mind that she sort of wants to get rid of me.

‘Let’s go down to the willow,’ says Keek.

‘What’s the willow?’

Keek laughs. ‘It’s a tree.’

The willow grows in an empty block a few houses down the road. The rest of the yard is dandelions and clumps of grass. Through the screen of delicate weeping willow fronds, the light changes and we’re in some other, watery realm. But the lumpy bark is gnarled and comfortingly solid, the grass right up to its feet. There’s no way Keek and I can reach around the trunk to touch hands, but it’s nice to try, to press my cheek against the bark.

We sit, backs to the trunk. Time ticks past. I don’t want to miss out on Aunty Jean’s tempeh burgers with caramelised onion – ‘tampon burgers’ she calls them, but they’re so good even that can be forgiven. But I do want to see in Keek’s house. What’s the big secret? His mother can’t be more embarrassing than mine.

‘Why don’t you want your mother to meet me? Don’t you think she’ll like me?’

‘It’s not that.’

‘What is it then?’

Keek fiddles with the cigarettes. Flicks the lighter a few times. ‘Nothing.’

‘Do you reckon I could come in then and wash my hands and rinse my mouth out with toothpaste?’ I have my body spray, but am paranoid about Mum smelling smoke on me, although she seems oblivious so far. ‘Please?’

I part the willow curtain and head off.

Keek’s place is even weirder than mine. A lot weirder. And it smells . . . odd. Lights are on, but they cast only a dim glow, as if electricity doesn’t have the power to penetrate the gloom. When my eyes adjust, I see that the walls are hung with animal-print blankets: lions, tigers, elephants. Heaps of them. All different, but the same colours: brown and yellow and black. I feel like I’m walking into a cave. A cave crowded with furniture. The lounge is a corridor through cabinets and chairs.

‘Mum buys and sells things,’ Keek says. ‘You know – eBay.’

I don’t know, but I nod.

The large dining-room table at the end of the room is dominated by a statue of a bare-breasted black woman wielding a spear.

‘Who’s that?’ I ask.

‘Candace, warrior queen of the Kushite Empire. Fought the Romans in 350AD.’

Candace is dangerous, and ready to run – even though her feet are moulded into the platform she balances on. ‘Did she win?’

Keek shrugs. ‘For a while.’

There’s a blanket-free wall dotted with hanging statues of Mother Mary and Jesus on the cross, and under them Keek’s mother is asleep on the couch, her fair hair on the pillow.

‘You don’t have to sneak, she won’t wake up.’

But I do sneak, fearful of disturbing her.

The hall is lined with photographs and I stop in the half-light to look more closely. A large framed Jesus with his bleeding heart is surrounded by family portraits, school photos and holiday snaps, all framed and arranged. Some enlarged. One face is in every photo. Like Keek, but not Keek. The same curly mass of hair, but more blonde. The same blue eyes. Before I can ask the question, Keek says, ‘My brother, Matthew.’

‘I didn’t know you had a brother.’

Keek leans against the wall and a sigh comes out of him like he’s tired enough to cry. He stares at the photos, takes a big breath as if he’s going to launch into some long story, but all he says is, ‘He died.’

The hallway shrinks, narrow and airless. That’s what Keek’s house smells of – more than dust and Jesus and toast – it smells of sad. The kind of sad that won’t go away. I feel like hugging him, but he doesn’t look like he wants to be hugged. He looks like he wants to escape.

Keek pushes himself off the wall and away from my sympathy. ‘I was only seven when he died.’

‘How old was he?’

‘Seventeen.’

‘That’s young.’

‘Yeah. Bathroom’s through here.’

The bathroom is a shock, like a sudden loud noise: brightly lit with all white tiles.

‘God,’ I say.

‘Sorry, should’ve warned you. You have to close your eyes and then let them adjust to the light. Dad’s a fanatic for a clean bathroom.’

‘And I thought my family was weird.’

Keek opens the medicine cabinet and reaches for the mouthwash. A stack of bottles and boxes meet my eyes. Pills, shoved in to fill the whole shelf space.

‘What’s all that?’

‘It’s Mum. She has – I don’t know. Anxiety or some shit. All sorts of stuff.’ Keek shuts the mirrored door and I rearrange the shocked face I see reflected there. He hands me the hyper-blue bottle. ‘Use that.’

I rinse my mouth and wash my hands, pondering the strangeness of Keek’s family. No wonder he’s a loner at school. I’m dying to ask more about his mum, asleep out there on the couch that’s made up like a bed. So fast asleep that we can walk through the house talking and she doesn’t wake up. But I don’t ask. I know how much Keek is already risking, just to show me.

‘Come out the back,’ he says.

The back garden is like nothing I’ve ever seen before: a network of creatures in cages. Dogs. Cats. Birds. Chickens. There’s a concrete pond with a tortoise and the area around the pond is caged. Another caged pond has strange lizards crawling about underwater. Little monsters with giant grins. ‘What are they?’

‘Axolotl.’

He looks at me. I look back at him.

‘Mexican salamanders,’ he explains. ‘Mexican walking fish?’

‘Oh, right,’ I say, as if they’re not completely freaky.

Inside a cage with two huge cockatoos, three cats are fast asleep; others prowl. The cages are connected by wire tunnels. ‘Don’t the cats eat the birds?’

Keek seems surprised, as if this were a novel idea. ‘No. Not that I know of. Check this out.’ He shows me an above-ground pool with metal sides, filled to the brim with water and weeds and algae. Giant goldfish crisscross under the surface.

‘Wow.’ A weedy concrete path winds through the maze of wood and wire. ‘Are your dogs always caged up?’ I can’t help but ask.

‘Nah, hardly ever. Only when we’re all out.’

I don’t mention the fact that his mother is, technically, home. He lets the dogs out. They’re old; two fat labs that ignore me, waddling off to the house. Keek points to the black. ‘That’s Cap, short for Captain Goodvibes, and the yellow one’s Charlene. They’re Dad’s dogs, really.’

‘Did he build all this?’

‘No.’ Keek’s attention slides off the dogs to the drawn blinds. ‘Mum.’

‘Pretty handy.’

‘Yeah. She spent a lot of time out here when I was growing up. I didn’t know how weird it was until I started going to birthday parties and saw other people’s backyards.’

‘All these cages, aren’t they sort of . . . cruel?’

‘Mum hates the thought of anything being in danger. That’s what the cages are for. To keep everything safe.’

‘What happened to your brother?’

Keek’s fingers curl through chicken wire. ‘He . . . We used to live

at the beach.’ A fat cockatoo unfurls its crest and lays it flat again.

Keek is so . . . stricken, I don’t even want to know any more. ‘Keek—’

But he ploughs on, his forehead pressed against the wire. ‘He snuck off. Matt. Down to the surf beach. Got pissed with his mate, Steadman. Rick Steadman.’ The cocky crests again and flaps its wings, making me jump. Keek glances up at the bird. ‘Just a bad rip.’

‘Sorry.’ It seems a stupid thing to say.

Keek lets go of the wire. ‘Thanks. Mum and Dad . . .’ but he trails off and changes the subject. ‘Uncle Rob reckons I’m a lot like him. Matt. Anyway, doesn’t matter.’

The cocky spreads its wings again and squawks a drawn-out raucous, ‘Crack.’

We stand there for a while, leaning against the wire, saying nothing. The cockatoo turns away to preen, dragging his hooked beak down yellowing feathers, and Keek says, ‘Where’s your dad?’

I stare at the big safe fish swimming in their pool. ‘Promise you’ll never tell anyone?’

‘Okay.’

‘Cross your heart?’

He crosses his heart. ‘Cross my heart.’

‘Mum doesn’t know where he is. One-night stand.’ I glance at Keek, to gauge his reaction. ‘I’ve never met him.’

‘That must be hard.’

‘Yeah. His name’s Michael Ellison and he lives in Sydney, or he used to. He went there before I was born. When I was little, Mum told me he was off on an adventure and I believed her. Aunty Jean told me the truth.’ It still makes my throat ache to say it. ‘He didn’t want to know about me.’

Keek is offended on my behalf. ‘Why did she tell you that?’

I bob down and stick my finger in the cage to stroke a cat. It shifts its ears. ‘Cos.’

I don’t want to tell him how I’d kept asking and yelling and blaming. I’d thought Mum was keeping him away on purpose. I was only thirteen. She was angry with Jean, for ages, but they’re over it now.

‘Mum reckons he was young. Panicked. Ran away. She’s tried to find him but – anyway, no point, really.’

‘That sucks.’

‘I suppose so. If anyone asks, I say he lives in England.’ The cat’s fur is soft. Soft as a rabbit’s. ‘But sometimes I think he must be dead. Or that if we did find him, he still wouldn’t want to know me.’

It feels strange to talk about my dad. Mum and I rarely do.

My voice drones on, almost as if it isn’t connected to my body. ‘I made up stories about him and did drawings, when I was little. He was sort of mixed up with Aslan from the Narnia Chronicles – appearing in the nick of time to rescue me.’ I close my eyes, embarrassed to have blurted my childhood ridiculousness. No wonder my dad doesn’t want to know me: I’m an idiot.

‘Is that why you can’t ride a bike?’

That opens my eyes again. ‘What?’

‘Is that why you can’t ride a bike? Because your dad didn’t teach you?’

The cat scares me by yawning and stretching. ‘Trust you to relate every single thing to riding a stupid pushbike.’ Keek’s garden is freaking me out. I can’t breathe. ‘I’ve got to go.’

‘I’ll dink you home.’

‘Nah, I’ll walk. I’ll see you tomorrow at school.’ I picture Keek going inside, making himself a sandwich. Does he chat to his sleeping mother? When will she wake up? ‘Thanks for . . . you know. Showing me around.’

There’s a swarm of Aunty Jean’s chatty friends at the barbeque. Only a few have kids and they’re all much younger than me. All the children have two parents of various genders; one little baby has two dads and two mothers. Everyone’s normal except me. It puts me off my tampon burger.

‘Cheer up, Shamrock,’ says Aunty Jean, toasting me with a wave of her champagne. It sploshes out, sparkling to the grass.

I complain, a lot, and we leave early. As soon as we get home, I check our people search and finders accounts on the computer to see if anything has come up about my dad. Mum looks over my shoulder. ‘Any luck?’

‘No.’

‘I’m sorry, love.’

‘Doesn’t matter.’

‘I could try directory assistance again?’

‘Maybe. It’s probably a waste of time. Can I go on Facebook?’

‘No. Jean keeps checking; he’s not on Facebook. And you know how I feel about it, I—’

But I don’t want to hear. I grab my sketchbook and a few greyleads, call for Lucille and go outside. Leaning against the old familiar trunk of the Golden Ash, I look out into the garden – Mum’s jungle of vegetables mixed in with shrubs, herbs, flowers and weeds. Plenty of weeds. Dandelions with their clocks and forget-me-nots with their clinging seedy tendrils creep over the paths and through my memories. I try to capture them with the pencils, but without colour they seem bleak, and lonely, as though growing in the shadows of a forsaken place.

I look up. Bespeckling sunlight filters through the new spring leaves as if the whole canopy is lit from below; late sun, the kind of light that will soon disappear. I hoick myself up, but can’t hang on and run up the tree like we used to – instead, I strain and clamber and almost give up, but once I’m on the old broad branch, it’s worth it; the sweet smell, the quietness, the strange slow butterflies with their tiny brown lace wings.

But I could do with a cushion. I’d forgotten how uncomfortable it gets.

Mum calls me in for dinner, but I say I’m not hungry. Lucille, however, deserts her post at the foot of the tree and follows Mum inside, slowly. With a heart-lurch I see the dog’s not sturdy anymore. Her back legs are thin and rickety.

It’s dark. I’m bored and starving and my bum’s gone numb. I climb down (which isn’t as easy as it used to be either) and go inside to make myself a toasted cheese sandwich. I don’t want any big deep and meaningful about my absent father, but not talking has started to feel stupid, so I say, ‘Mum, what was Keek’s mum like at school?’

‘Maria Yoxon? She was a spunk. Blonde hair. Cute little nose – like Keek’s, actually. All the boys were crazy about her. Jean always called her Oxo. Only behind her back, mind you.’

I try to imagine the lump of snoring blankets I’d seen being the hottest girl at school, but it’s impossible.

‘Her dad was scary, though,’ Mum says. ‘They were staunch Catholics and she wasn’t allowed do stuff that most kids took for granted.’

‘Like what?’

‘Oh, lots of things.’

‘I know how she felt.’

Mum ignores my bait.

‘Were you friends?’ I ask.

It isn’t like my mum to hedge, but her eyes slide away from me. ‘Not especially. I was better friends with Dave.’

‘Dave?’

‘David McKenzie. Keek’s dad.’

‘You didn’t go out with him, did you?’

‘Have you had enough to eat? There’s plenty of left over—’ ‘So you did go out with him?’

‘We were friends. I thought maybe . . . but then Oxo liked him and that was that.’

‘Did you kiss him?’

‘No.’

Is she blushing? ‘You sure?’

‘Have you kissed Keek?’ she counters.

I’m not convinced, but do not want to get into a discussion about me and kissing. Should I kiss Keek?

‘Have you?’ Mum says.

‘No. Shut up.’

‘No need to be rude—’

‘Keek’s mum is strange. She—’

‘Don’t tell me about Keek’s mum’s private weirdnesses, Clover. I’d hate to think you’d tell anybody mine.’

Is she kidding? I’d rather die. Unfortunately, most of hers are right out there on the surface for anybody to see. But all I do is shrug. ‘Sure.’

It’s only later, in bed, that I think of Mum and Aunty Jean dissecting everybody they know and not only discussing private weirdnesses, but rolling around laughing about them. I feel annoyed. Mum is always encouraging me to open up to her about things but now that I wan

t to discuss something, she shuts me down. I get up and pad down to the lounge where she has her CDs out for a change – Portishead. The shy, silky voice of Beth Gibbons laments softly from the stereo.

Mum’s lying on her stomach flicking through an old photo album, feet in the air, a glass of red wine at her elbow. ‘You should be in bed, Clover,’ she says when she sees me.

‘What are you doing?’

‘Nothing important.’ She closes the album and sits up. ‘Anything I can do for you?’

‘Mum, I need a mobile phone.’ Because suddenly it burns how badly I do. ‘It isn’t fair that I’m the only person on the planet who doesn’t have a mobile phone.’

‘Where did that come from?’

‘It comes from the fact that I need a phone.’

‘Why?’

The right phone will give me unfettered access to Facebook, for a start. ‘Everyone has one. You don’t need to need one to need one. I’m not a little kid anymore.’

‘Well, get yourself a part-time job to pay for the credit and I’ll think about it. Now come on, go back to bed.’

‘What were you looking at?’

‘Photos.’

‘Is Keek’s mum in them?’

‘Yes.’

‘What about an iPod touch?’

‘What do you mean?’

‘Can I have an iPod touch then? If I can’t have a phone?’

‘Maybe for your birthday, Clover.’

‘Is that her?’

Mum stares at the photos and disappears into her thoughts; back to school, I guess. Gently shaking herself, she points. ‘That’s Maria and that’s Dave.’

I’ve seen Mum’s school photos before and know where she and Aunty Jean are in every picture, but now I pore over the pages, trying to recognise Mr and Mrs McKenzie in the different years. ‘And that’s her?’

‘Yep. That’s her.’ Mum drains her glass. ‘Come on, Poppet, I’m going to bed now.’ She closes the album and tucks it into its slot on the bookshelf.

‘You were prettier than her, Mum,’ I lie.

Mum puts her arm around me and gives me a squeeze, shepherding me off to my bedroom. ‘Thanks, Clover, but there was something about Oxo. We always thought she should’ve been a movie star.’

Cracked

Cracked