- Home

- Clare Strahan

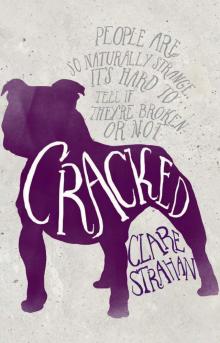

Cracked Page 6

Cracked Read online

Page 6

Keek slaps at a mosquito. ‘Cho’s grandparents used to live by a big river in Burma.’ He claps at the mozzie, and seems thoughtful. ‘Burma’s called Myanmar now. Imagine that – you leave your country and they change the name while you’re gone, so in a way, you can never go home.’ He gets up to go poking further along the trunk. ‘The river had dolphins in it.’ He drags up a big stick to see if he can reach the other bank and, no doubt influenced by Cave’s Euchrid Eucrow, thickens his voice into a Southern American accent. ‘No dolphins in this here crick.’ He amuses himself by repeating, ‘Mah dolphin crick.’

I tell him to shush and, as my mum would whisper, just sit ‘in its shadowy heart’. After a while, probably lulled by the peacefulness, I say, ‘When I was little, Mum used to sing songs to the undines.’

‘The what?’

I’m glad we’re in shadow. ‘Water-fairies. Undines in the water, sylphs in the air, gnomes deep in the earth, and fire fairies. I never liked the fire fairies’ proper name.’

‘Oh yeah?’ Keek has his sceptical eyebrows on.

‘Salamanders.’

‘You can get axolotl called fire salamanders,’ he concedes. ‘People don’t swim in this, do they?’

Alison and I used to paddle down here, when we were little: with Mum, of course. ‘Probably not,’ I say. ‘It’s not really deep enough for swimming, anyway.’

Keek points. ‘Look.’

An echidna. We freeze and it scrabbles to dig its face into the dirt before freezing too, leaving only spines for us to admire. After a few minutes, Keek says, ‘Bored,’ and pushes me into the shallow water; I grab his shirt and pull him in after me. We wrestle, despite the rocks, and his skin against mine is warm even in the freezing water. He pushes past me to clamber out.

Did you want to kiss me? I want to say, but I never will. I mean, he would’ve already, wouldn’t he, if he wanted to? And after all, I don’t want to kiss him. I mean, I would’ve already, wouldn’t I, if I wanted to?

‘The anteater’s gone,’ he says.

Everyone was nervous about the end-of-year exams, even Mum, even Alison Larder, but I quite liked being sure there was at least some purpose to studying. Not that I studied much, but I think I did all right. I bet Alison gets all A-plusses. Lying under the Golden Ash, feeling the freedom of the school holidays lift me like a helium balloon to float up through the buttery leaves, it makes me feel happy to imagine she did.

Keek and I are supposed to be going to the movies at some stage, but he hasn’t turned up. Perhaps his mum won’t let him out. Sometimes she freaks out, or has ‘episodes’ that make him feel like he has to stay home.

‘I can’t go,’ he says to me. ‘She’ll kill herself or something.’

But any time I go there – if she’s awake – she’s as nice as pie, if dishevelled, and a bit bloated, you know, in that unhealthy sort of way. But she’s still beautiful and her hair is still blonde. I wonder if she dyes it. She must.

I’ve never seen anyone smoke so intensely. When she’s not asleep on the couch, she sits on their back porch staring at the cages, chain-smoking.

‘We grew up around here,’ she’s told me a few times now. ‘I never wanted to move back here. I wanted to live in Queensland. Or Paris. But David . . . when . . .’ She butts out her cigarette and reaches for another. ‘He didn’t work for nearly two years, you know. Hopeless. This is his uncle’s house, you know. I never wanted to move back here.’

I find myself almost hypnotised, but Keek always drags me away. If he isn’t allowed to go far, we hang out at the willow and read aloud to each other. Mum lent him The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy and he’s obsessed. It is funny.

Whenever we do ride off, Mrs McKenzie shouts, ‘Look after my boy, Clover,’ and Keek says, ‘Ignore her.’

My mother annoys me by being on the phone.

‘See how I need a mobile?’ I complain.

She cups the receiver and mouths, ‘You’ll have to wait.’

‘Mum, I need to call Keek.’

She shakes her head and says, ‘Sorry, I missed that.’

‘I’ll just walk there then.’

She nods and waves me away with a distracted air kiss.

Mrs McKenzie says hello and smiles, but her voice is croaky and she doesn’t take off her sunglasses. Never a good sign.

‘We’re going to the willow,’ Keek tells her.

‘No.’ She crosses her arms as if holding herself in. ‘Not today. Stay on the property.’

He turns his back on her. ‘I’m going to the shed.’

I follow. ‘You all right?’

We hide behind the garage and light up. Keek keeps a lookout. ‘Yeah, am now.’

‘What happened?’

‘Dad.’

‘What’d he do?’

‘Said he was leaving.’

‘No shit?’

Keek scrapes mud off his shoe against an old brick. ‘No shit.’

‘Is he?’

‘Nup.’

‘Well, that’s good. Isn’t it?’

‘He never does.’ Keek kicks at the brick. It rolls over and there’s a worm, squirming in the light.

Keek and I stare at the worm, now on his palm. Keek seems entranced but I don’t find worms that fascinating.

‘You right?’ I say.

He grunts, softly, and the worm flips itself over.

I leave him to it and venture into the garage, pulling up the roller door to let in more light. The garage smells musty, oily. Keek’s a million miles away: he’s in the driveway now, watching the worm wriggle across the concrete, heading for the grass. I fossick around. There’s gardening stuff, camping equipment covered in cobwebs, a stack of old wooden crates full of empty brown bottles with no labels, a wall of hanging tools that don’t seem to have been used, a meccano-stack of old pushbike parts and – score! A whole box of aerosol paint, blue, red, black, green, gold, silver, white, never even used by the look of them. Keek squats next to me.

‘Where’s your worm?’ I ask.

‘It wasn’t my worm,’ he says.

I pull out a can – black. ‘What’s all this?’

‘That’s Dad’s uncle’s stuff. Uncle Andy. He restored pushbikes for a hobby, and Dad still goes on about his home-brew. He made wine, too – there are still a few bottles of Uncle Andy’s Elderberry in the pantry, but I don’t think anyone’s game to open them.’ He lifts a rusty crossbar from the stack and a big black spider scuttles off, scaring the crap out of both of us. Keek says, ‘Jesus’ and drops the crossbar on a bunch of garbage bags filled with old clothes and shoes. ‘I guess he spray-painted the bikes when he was finished fixing them up. He was pretty old. He died when I was about nine. That’s why we got this house.’

‘Do you remember Marilyn Lepace?’ I say, peering into the paint-can box for spiders and hoping there aren’t any.

‘Who?’

‘Marilyn Lepace.’

He picks up a handlebar to poke at a cobweb. ‘Nup.’

Marilyn Lepace was a year above me and never so much as glanced in my direction until Sutcliff sent me to Berty for refusing to take off my beanie – and she was already outside the principal’s office, lounging against the wall. She beckoned me to the window that looked out on the quadrangle.

‘Check it out,’ she said with a sneery curl to her lip. ‘My farewell to Fernwood.’

I stared.

‘Your mouth’s open.’

I shut my mouth.

They’d tried to scrub it off, but in huge red lettering outlined in black on the drama studio wall, Marilyn Lepace’s ‘FKU BERTY’ rose from a lumpy bed of skulls and refused to be denied. I was mesmerised: the chunkiness of it. The grunge. The pulpy-red blackness and the pale bone. The pretend flashes of light really worked. It was the coolest thing I’d ever seen.

The principal’s door opened and he motioned me inside; then eyed Marilyn warily. ‘Your mother is on the way.’

Marilyn held my eye. ‘I’m expelled

,’ she said.

All I could do was nod, my blood racing with a strange, admiring thrill.

I pick up a can and flick off the lid. Adrenaline rushes up from the earth and into my body, my arm, my hand holding the paint. ‘I want to spray this can.’

‘Where?’

‘Anywhere.’

‘Not in my parents’ garage.’

‘What about the road?’

‘Black paint on the road, it won’t work. You’re an idiot.’

I head out to the road. ‘I don’t care. I have to spray this can of paint as soon as possible.’

‘An idiot with a spray can,’ Keek says after me. ‘Just what we need.’

An aerosol can is no pencil. No paintbrush, either. It’s alive. I’m shocked by the force of the paint from the nozzle. By how wide it sprays. I’ve read that graff artists get special caps and now I know why. Keek’s right, it does disappear on the road. But I don’t care.

It’s intoxicating.

Keek hovers on the footpath. ‘What are you writing?’

‘My tag.’

‘You have a tag?’

‘I do now.’

He looks down at my scrawl. ‘Kandas,’ he says. ‘What’s that?’

‘You know, Candace, warrior queen of the Kushite Empire.’

‘That’s not how you spell Candace.’

‘It’s a tag,’ I say, mildly scornful. ‘You can’t spell it right.’

Keek yawns. ‘I don’t like it. No one will get it.’

I straighten and stretch my back, running a curious eye over the fence across the road. ‘I’ll get it,’ I say.

Keek smiles when he sees me waiting on the footpath. His expression darkens when he spots my criminal backpack. ‘What’s in there?’

‘Paint.’

He crosses his arms in a pretty good impersonation of Mrs Sutcliff.

‘No one will care if I practise down there,’ I reason.

It’s taken days of sketching and mostly invisible road-scribbling to master ‘Kandas’, and how better to amuse myself at the bowl over the summer holidays?

‘Or would you rather I hung out under the railway bridge?’

‘Don’t be an idiot.’

‘Don’t call me an idiot.’

‘Don’t act like an idiot and I won’t call you an idiot.’

I hold it out to him. ‘Are you going to carry the bag or not?’

At first I feel embarrassed, experimenting with Cho and the others being here, but they’re busy practicing some new trick they’ve caught off the internet and barely pay attention to me. I feel sweaty and strange, as if the police might spring out from behind the bus stop. My first tags are horrible, but a flat section of the bowl falls prey to my freeform experiments and some of it doesn’t look too bad, considering the dinosaur paints I’m using.

‘Vandalism,’ Keek calls it.

‘Graff,’ says Cho.

‘Art,’ I insist.

Well, it will be.

It’s the dawn of Year Eleven and I groan as I drag my bag on my shoulder and head to the front door, half-dreading and half-excited to see what the new year will bring.

‘What about we try homeschooling?’ Mum asks, looking worried as hell about that idea.

‘Bit late, Mum.’

‘Oh, Clove, I don’t want you to be ground into sausage meat.’

My mum might hate television, but she loves old DVDs and last night we watched Pink Floyd’s The Wall – it’s obviously had a lingering effect. I fell asleep before the end, but I saw the scene where the school kids get put through the meat-mincer. ‘I don’t want to be homeschooled,’ I say, and give her a goodbye peck.

And that’s true. God only knows what kind of freak I’d end up being if my mother were the only person to have influence over me.

Looking down at school from the top of the hill is like witnessing an architectural crime scene. There’s more art in a stop sign, in the necklace of mediocre tags strung around the art room portables. Asphalt, concrete and fibrocement; Mother Nature caged and dissected into squares of tanbark, nearly all the trees pushed to the edges. They’d rather we die of boredom than climb a tree.

Like a chink in my armour, Keek swings into step next to me.

‘The Year Sevens look about ten,’ I say. ‘I want to tell them all to run home and stay there.’

‘They’d get bored.’

I shoot him a look. ‘Yeah? Well, Mum reckons boredom is the flip side of creativity.’

‘Yeah? Well your mum’s on the flip side of reality.’

‘So you don’t think school’s priming us for neoliberal servitude, like Mum says; having the creativity crushed out of us, shoving us into consumer boxes, little cogs in the economic machine?’

Keek gives me two thumbs up, saying, ‘I don’t think anything,’ and splits off to catch up with Cho and head to their elective.

My VCE art teacher is brand new to the school as well as to me. Sutcliff introduced her at assembly as Ms Yamouni and that’s all the class knows about her. We sit outside the art room waiting, tossing around the rumour that she’s from Iraq.

Four girls slouch against the wall in the corridor and the rest of the class spills out from there.

‘What? Like falafel?’ Rosemary Daniels says, and laughs.

Presumably, Rosemary has given up SingStar. She has gorgeous blacker-than-black dyed hair that never grows out at the roots. Her posse of cool girls laugh at her joke, but they don’t have to laugh and that gives them their edge. Their names are Natalie, Katie and Ellen, but Keek has secretly named them Parsley, Sage and Thyme: the Herbs. Ellen/Thyme’s dress is so short, any movement flashes her cool undies – the brand Mum won’t buy me because of some capitalist crime she reckons the company committed against their workers.

Pete Tsaparis laughs too loud and says, ‘She’s probably a terrorist.’

‘Don’t be a dickhead,’ I tell him.

He gives me a shove. ‘Shut your face.’

Rosemary says, ‘She taught with a falafel in her hand,’ like a voice-over, and people laugh. It’s not that she or the other three are especially thin, or even beautiful. Not especially. Or even that funny. But they always manage to be in the same Home Group while the rest of us are shuffled around, and they never seem to need anybody or get excited about anything except each other. Everybody is in love with them – there are Herb-clones all over the school. It’s the Asian girls who start trends, but somehow it’s the Herbs who get crowned queens of style. Even Keek observes them from afar.

Rosemary wants to become a fashion designer, so I guess that’s why they’ve elected to do VCE Art.

‘Yes, like falafel.’ The voice is rich and has a slight, warm accent. We turn collectively and there’s Ms Yamouni with her incredibly thick dark hair tied in a knot on top of her head, and her oval face and her beauty spot. She’s petite and rounded and when she walks past me, smells of acrylic paint and rose oil. I wonder how long she’s been listening to us. She nods to Rosemary and says, ‘What’s your name?’

‘Rosemary.’

Ms Yamouni’s smile shows her big, square teeth. ‘Ah! Like roast lamb?’

The class shifts uncomfortably. There is something scary about Rosemary Daniels and no one wants to get on the wrong side of her. But she laughs and says, ‘Yeah. That’s how my mum makes it,’ and we all breathe out.

‘Well, I’m a vegetarian, Rosemary, but I won’t be forgetting your name. Not so sure about all the rest of you, so you’d better answer the roll and then we can get on with business.’ She unlocks the art-room door and we pile in. Her voice rises up over our noise. ‘And while I’m calling the roll, I want you to move all these tables into a circle. Do you think you can manage that?’

Just as well every art class is a double because it takes about fifteen minutes for us not to manage it well at all. I groan. First amateur theatre, now furniture removal. When she’s given us a lecture about respecting the space, equipment and art supplies, she makes

us put on our smocks, roll up our sleeves and sets out a dozen bottles of acrylic paint – all blue – and lays out a slab of butcher’s paper.

‘Just one colour?’ asks Rosemary.

‘Just one.’ Yamouni wipes her hands. ‘Prussian blue was created by a Swiss paint-maker called Diesbach. Funnily enough, he was trying to make red, mixing plant ashes that had been soaked in water, called potash, and iron sulphate, which he would have called copperas and might have been made from blood.’ There’s a collective squeamish lament.

‘Blood?’ I ask.

‘Blood,’ she replies. ‘It’s only been a relatively short time that artists have had the privilege of going to a shop and buying pre-mixed paint off the shelf. In the past, many artists were scientists, too: chemists, creating new pigments in their search to express adoration, beauty, pain, the human condition, our aspirations.’ She takes a deep breath, as if standing by the ocean. ‘Blood, animal fat, all sorts of things. Luckily for us, when Diesbach tried to improve his pale red gone wrong because of his cheap ingredients, he heated it to concentrate the colour and accidentally discovered this stunning blue instead. At the other end of the blue spectrum, ultramarine was made from precious stone, lapis lazuli – quite rare and at times, in some places, more valuable than gold.’

Yamouni instructs us to pour a blob of our colour wherever we like on our paper. ‘This is acrylic paint, of course – all synthetic. Not too much,’ she says. ‘But don’t be stingy, either.’

Pete Tsaparis makes a gross phallic gesture with the bottle, then squeezes so hard it slurps onto the floor.

Yamouni says, ‘No.’ She takes it off him and hands him a roll of paper towel. ‘Clean that up and go and sit down. I meant what I said. If you can’t respect the art supplies, you can’t participate. But there’s plenty to be learned by observing: sit over there and watch.’

I can tell Pete wants to arc up, but he obviously thinks better of it and deflates. Everyone knows he’s on a behaviour card after almost getting expelled for punching Lisa Dalboni’s younger brother Mike after the cross-country run.

Cracked

Cracked