- Home

- Clare Strahan

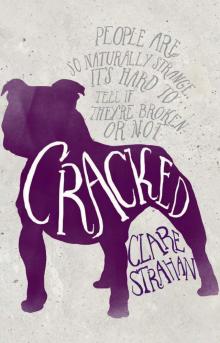

Cracked Page 10

Cracked Read online

Page 10

‘It’s this or eventually restump our house,’ he yells over the scream of the chainsaw.

‘Not good enough,’ Mum yells back.

‘Piss off,’ he says, and disappears inside, slamming the door.

Mum rings the council, but the tree is within thirty metres of their house and there’s nothing she can do.

It’s horrible. A murder. The noise is like torture. To get away, we head into Fernwood, but the tree haunts us. Everything around me is smothered in concrete and asphalt. The poor trees down Main Street poisoned by traffic. There are gardens in Fernwood, but every one is trapped and tamed; the planters outside the shops are littered with cigarette butts.

I take in the ugly buildings, the signs – who decides it’s okay to turn the earth into instructions, into concrete squares? Into poison? Why is everyone walking around as if nothing is happening? As if the planet isn’t groaning and shrieking. As if, like the tree, it’s too inconvenient to save.

When we get back, the stump is surrounded by sawdust and debris and a great unruly pile of trunk-rounds, like giant checker pieces. Branches are bundled up, ready for green rubbish collection, and there’s a mountain of mulch.

Mum bursts into tears.

Sitting up in bed later that night, I pull a sketchbook and my art journal out of my bag. Yamouni wrote transform your love into art and let art transform the world; but how is my art going to transform the world if I’m the only one who ever sees it? I can’t just go out scrawling ‘Save the Creek’ everywhere. Or can I? No: I’d rather tell a story that somehow shows what’s really happening to the corridor, if I can. Craig told me I’ve got a good eye: if I use freestyle colour and make smart stencils, maybe I can do something quick enough not to get caught, but good enough to at least make people think.

At least I’ll have tried.

I make rough sketches of the key players in the drama: the trees, of course, and the birds, the echidna and the orchids. The creek remains passive, the source from which they draw their sustenance. And how to represent the enemy? I start off with a caricature of whatshername, the MP, but it’s not her fault – she’s just the patsy who had to come out and say something reasonable for the local paper. It’s more sinister; the real reason the planet is covered in tar and pollution. Politicians big and small are puppets, their strings pulled by corporations with investments in everything bad: war, oil and, Mum’s pet hate, consumerism. A guy in a suit emerges, a dollar sign where his heart should be.

Somewhere along the line we seem to have let ourselves forget that nature is necessary for its own sake, not just for what we can get out of it. We’ve forgotten what’s real, our source. We can’t get rid of everything beautiful and living and free. Can we?

Mum knocks softly and I close the sketchpad. ‘Come in.’

‘You’ve been crying.’

She hugs me, and Lucille shocks us from our wallowing by making a jump for the bed, chaotically scrabbling at the bedclothes and scratching my leg. Her anxious face is so pathetically adorable, we laugh. Mum helps her up.

‘Ouch,’ I complain, rubbing the welts. ‘Look what you’ve done.’

Lucille collapses into comfort, puts her head on my thigh and stares up at me with raised eyebrows.

‘You silly old lunatic,’ I say.

Banksy wasn’t kidding when he said mindless vandalism takes some thought. A few weeks after the death of the tree, I show Keek the stencils I’ve slaved over, carefully slide them into my art folio, put it next to my loaded backpack, and float the idea of a midnight trip to Fernwood.

‘Don’t be an idiot.’

I swear he’s Sutcliff’s illegitimate love-child.

I match his folded arms. ‘I’m doing it Tuesday night, whether you come with me or not.’

‘Bullshit.’

It’s Tuesday night.

I’ve been lying in bed for hours, sweating, crushed between a heavyweight blanket of guilt and fear and the adrenaline of an unstoppable vision. And I’ve told Keek that I’m doing it, so I have to go through with it. The tension drives me out of bed.

Getting dressed sounds unbearably loud. Lucille, deaf as a post the rest of the time, scares the crap out of me by jumping off Mum’s bed and coming to investigate. I pray she won’t bark when I leave. ‘Good girl,’ I whisper, give her a kiss and sneak out the door.

The street is quiet, dark. I’m cold. Scared to leave the porch. The thought of walking on my own even to the end of the block seems impossible. Keek riding up out of the dark makes me startle, but I could cry with relief.

‘You’re really doing it?’ he asks.

‘I really am,’ I say, and feel a different kind of fear.

He offers up his handlebars. ‘Come on then.’

Keek shoulders my backpack. I didn’t kiss him when he fitted these footrests, so I suppose I shouldn’t kiss him now. I climb on and lean back, the wax cardboard folio across my knees. It’s good to feel him there. He’s warm.

‘Where?’ he says.

‘Supermarket.’

‘We’ll get caught.’

‘No we won’t.’

I feel sick, riding there, and the folio is an aerodynamic disaster. Finally, Keek pulls up in the shadow of a shop doorway across the road from the supermarket. I get off and he passes me the backpack.

The supermarket is on the corner, and it’s the Main Street wall I’ve been dreaming about. With stencilling of any kind, whether it’s for screen-printing or a wall, the smoother the surface, the cleaner the line. The supermarket wall is perfect – I’ve felt it. It’s beautifully smooth, softly lit and calling to me.

Keek shakes his head. ‘It’s too visible.’

‘I’ll be fast.’

‘Start somewhere more private.’

‘Private doesn’t count. They—’ Anger rises like bile, choking me. ‘They think they own everything, but they don’t. They don’t own anything.’ A wild thrill rolls over me.

‘Who’s they?’ says Keek. ‘The dudes who own the IGA?’

‘Stay here.’ I run across the road. My hands are shaking and I can hardly get the stuff out of my bag. I’m glad I stole mum’s window squeegee to help stick the thin cardboard jigsaw of A3 stencils to the wall; I hope they’re as easy to peel off when I’m done. Stencilling SAVE THE CREEK steadies me. It looks good but the A4 letter-stencils are too small and messy around the outside. I’ll have to do something about that.

Keek rides up. ‘That’ll do,’ he says.

‘Wait, I haven’t done it yet.’

I work as fast as I can, running up and down the footpath, jumping up, wishing I had a stepladder. I strip off a stencil. Keek helps by putting it in the folio.

‘You’ve got to wait till they’re dry, it doesn’t take long,’ I say. ‘Or you may as well just chuck them in the bin.’

He waves one around. ‘Just hurry up.’

The tree is all right, covering its eyes with one twiggy hand – it’s faint at the top, but hardly any bleed. Soon enough the other stencils are down and the image makes sense: the tree cowering from a suit with a dollar-sign head, axe in hand. Not quite as I’d imagined it, but I don’t have time to fret. I spray a few highlights on the tree in green and purple, and blood on the axe, but before I can begin on my plan of painting in the creek freehand, a car turns the corner into Main Street. I make an ineffective grab for my gear and a can rolls away.

Keek hisses, ‘Leave it, run,’ and disappears. I bolt and hide behind the St Vinnies donation bin in the car park round the corner. The car drives on, followed by another one a few seconds later.

After a minute or two, I spot Keek looking for me and wave.

‘Let’s go,’ he says.

‘It’s not finished.’

‘It’s too risky. Two a.m. would be better.’

‘You promise you’ll come again? At two?’

‘Look at you,’ he says. ‘You’re a mess. Is that dry? I don’t want it all over my—’

‘Promise?’

/>

‘Not tonight.’

‘Another night?’

‘For fuck’s sake, yes, whatever.’ He wipes his hands on my paint-peppered hoodie and hoists my backpack onto his shoulder. ‘I’m tired, let’s go.’

‘I’ve got to sign it.’

Keek’s practically busting out of his skin with wanting to go, but he waits. Tagging ‘Kandas’ feels so good, the marker so fat and compliant and smooth, I want to do it again and again. But I need to be cool, and Keek is waiting.

I’m in the car with no chance of escape and Mum says, ‘So . . .’ in that particular way that lets me know that she’s about to say something I don’t want to hear.

‘Alison Larder won a national maths prize,’ I say, in a desperate attempt to distract her into a nostalgic ‘remember when’ about Alison. As an added bonus, Mum has a maths phobia. The mere mention of the word usually sends her into a cold sweat and off on some story about when she was at school and the follies of the mainstream education system.

‘I’m not blind, Clover.’

‘That’s good, Mum, considering you’re driving.’

‘It’s not funny.’

‘Well, excuse me for being amusing.’

‘I want it to stop.’

‘Okay, I’ll never make a joke again.’

‘You know what I’m talking about. I get what you’re doing and why you’re doing it. But it’s too dangerous. I want you to stop it.’

I stare out the window. ‘Mum, what are you even talking about?’

She pulls up outside the IGA. ‘That’s what I’m talking about.’ She nods to my piece, surrounded by tags now.

I want her to shut up about it. She hasn’t even said if she thinks it’s any good or not. It’s none of her business. ‘You’ve lost it,’ I say. ‘I don’t even know what you’re talking about.’ Lucky for me, there’s a beep and she has to move on.

‘So that isn’t your work?’ she says, pulling into a car park.

‘Shut up about it.’ I shove the door open and slam it behind me.

‘Where are you going?’ Mum calls after me, slamming her own door.

‘Walking to Keek’s.’

‘I mean it, Clover – it’s enough. And be home by dinner.’

I am home by dinner, but Mum is acting as though we’re in an angst-ridden SBS film and she’s the psychiatric patient.

I say, ‘Have you seen my hairbrush?’

She blurts, ‘It has to stop.’

I slam off to my room.

We sneak out whenever I can talk Keek into it. It doesn’t take much. I reckon he secretly loves zooming through the empty streets.

One night a bunch of scary local ‘lads’, all graffers, chase us down the street throwing stones and shouting, ‘Art fag’.

‘Congratulations,’ Keek hisses when they drop back, laughing. ‘Your peers.’

‘I’m not like them!’

‘Aren’t you?’

I have a vague stirring of excitement. ‘You want me to tag a train?’

Keek pulls up, traumatised.

‘Don’t worry. I haven’t got the guts.’ The street behind us is empty when I glance back. ‘And they know it.’

Apart from the lads and the occasional furtive weirdo, Fernwood is dead in the early hours. Mondays and Tuesdays are the quietest. I’ve never loved the moon so much before; never realised how bright it is, never missed it when it wanes. I can’t imagine getting caught, but the possibility fuels my pieces – which are getting tighter and smarter because Craig is full of good ideas about stencil design.

Each piece requires concentration, commitment and speed. I disappear into the act, into the strokes, into the wall. I guess it’s the same for Keek with his riding. Once he drops in over the lip of the bowl, there’s no turning back. Maybe that’s why he puts up with me. He understands the adrenaline. The whole-body flow. The art of it.

Periodic car-beeping from the local footy crowd is usually the only reminder the bowl-dwellers have that the rest of the world exists, but today is the first Saturday of the local footy finals and there’s a swarm of riders, skateboarders and rugged-up people everywhere. Excitement wafts from the oval and the roar is rhythmic, and passionate.

I hope Fernwood make it through. I’d love to watch Rob play in a grand final, but we’d have to play at another ground – to avoid the home-ground advantage – and I probably wouldn’t have the guts to make my way to another suburb to watch him. Not alone. I’m not game to get the tins out, either, with all these people about, so I play with chalk pastels. A landscape.

Cho takes off her helmet. ‘That’s actually good.’

‘Thanks, Cho.’

She runs her fingers through her hair then reties her ponytail. ‘Don’t get Keek into trouble, Clover.’

‘I—’ ‘Just, don’t.’ She flips her helmet on and clips it. Even wearing a bike lid she still manages to look supercilious.

Keek rides over. ‘What’s up?’

‘Nothing.’ Cho smiles at him. ‘I was just admiring Clover’s picture. It’s good, isn’t it.’

‘See,’ says Keek when she’s ridden away. ‘She does like you.’

‘Awesome,’ I say.

It’s the wee hours of the morning and I’m transforming a perfect factory wall, wonderfully smooth and ugly as sin; and there’s a good view of it from the train.

Keek sits on his bike and watches me; pausing his tuneless iPod-humming to say, ‘Hustle, CB.’ He fiddles with the iPod. ‘I’m cold.’

Keek had to manhandle his bike through a gap in the fencing so I’m freaked in case we have to get out in a hurry. Still, it’s the best piece I’ve done; a beautiful orchid, the evil suit snipping it off with a pair of scissors, a snatch of road in his other hand like money.

I’m almost done when Keek yells, ‘Fuck!’ and blinding lights are on us.

We freeze like rabbits.

From behind the light, a gravelly voice says, ‘Police. You, put that down, step away and face me. You on the bike, get off. Turn off that torch.’

We obey.

Stepping back, I accidentally kick a bunch of tins that crash, rolling around on the concrete. For a mad moment, I imagine running off.

‘My name is Senior Constable Boyd and this is Constable Ramidge.’ Big and square, Senior Constable Boyd steps over the last rolling tin to inspect my piece.

Constable Ramidge reminds me of Mrs Fitzpatrick, but Fitzy never wears a gun. ‘State your names,’ she says, and we do, like little robots. She jots them down in her notebook, double-checking the spelling.

Boyd runs his superior torchlight over my gleaming, dripping handiwork, unsatisfactorily unfinished. Ramidge gives it a cursory glance and says, ‘What a bloody pain in the arse.’

My fractured soul yawns open and fury rushes up to eclipse how small and stupid and scared I feel. ‘Visual art is a legitimate form of protest,’ I demand.

‘Picasso painted Guernica to wake people up to the horrors of the Spanish civil war. Banksy—’

‘Shut up, Clover,’ says Keek.

‘Car’s up there.’ Boyd points up the hill. ‘Go on.’

‘Where are we going?’ I ask.

Keek won’t look at me. I can feel how mad he is.

‘To the station where you can have a nice cup of tea and wait for your parents,’ says Boyd.

‘What about my bike?’

‘Fuck your bike, you little shit,’ says Ramidge.

‘Philip never did anything,’ I blurt. ‘He came so I wouldn’t have to be on my own. He thinks it’s a dumb thing to do.’

‘No, I don’t, Clover.’

‘Yes, you do.’

‘I—’

‘Keep your mouths shut and do what you’re told.’ Ramidge shoves Keek towards the car.

‘Hang on,’ interrupts Boyd. ‘Did you do any graffiti, Philip?’

I get the feeling Boyd doesn’t like Ramidge any more than I do.

‘No.’ Keek hunches his shoulders and says under his

breath, ‘She won’t let me.’

‘What was that you little smartarse?’

What is Ramidge’s problem? Nobody’s being rude to her. Boyd sighs and says, ‘Bring the bike along, son.’

The cops have opened the gate, but to fit Keek’s bike in their boot, they have to take out a bunch of orange traffic cones that they jam in the back seat with us. Ramidge is not happy.

We sit there like stunned mullets, divided by witch’s hats. I stare out my window and concentrate on not crying. When I turn his way, Keek is staring out his window too.

A stack of the traffic cones, heavy, chewed-looking and dirty, digs into my leg. I move them and Keek adjusts them back. I wriggle. He wriggles.

Ramidge says, ‘Been a busy little pain in the arse, haven’t you? My son’s quite a fan.’

Keek turns further away from me and I stare harder out my window.

Our parents arrive at the police station together. Mum’s wearing jeans and a plain black jumper. No pearls. Mr McKenzie is wearing jeans and a hoodie. Weird; they look young. Mum isn’t as visibly shocked as Mr McKenzie. Just worried. She has her hand on his arm when they walk in, sharing vibes of parental distress and for a flash of a second, I wonder what it would be like for my mum to walk in like that with my dad.

Mr McKenzie hands Keek a mobile. ‘She’s waiting for you to call.’

On the phone to his mum, Keek says ‘sorry’ and ‘fine’. A lot. While they talk, Mum keeps patting and hugging me as though I’ve been lost in the bush overnight. It’s claustrophobic, but I don’t mind, even when she kisses my paint-stained fingers and says, ‘Oh Clover, you’ve been smoking.’

Constable Ramidge, who suddenly doesn’t seem so keen on abusing us every ten seconds, goes off ‘to organise the rooms’.

They separate us. Keek disappears with his dad. He doesn’t look back. Mum and I are led into a bleak little room. Boyd sits on one side of the table, us on the other; Mum’s protective arm around me. Boyd shakes his head. ‘There’s a five-hundred-and-fifty dollar on-the-spot fine.’

Cracked

Cracked