- Home

- Clare Strahan

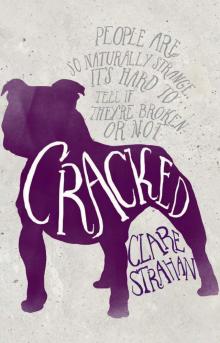

Cracked Page 11

Cracked Read online

Page 11

Mum is angry, but relieved. ‘Can I pay by credit card?’

‘Yes. Yes, you can. Look, you realise Clover will be charged with criminal damage?’

Mum bristles. ‘What does that mean?’

‘It probably means another hefty fine and definitely means a summons to front up to a magistrate at the children’s court. We don’t take kindly to vandalism in Fernwood.’

‘It isn’t vandalism.’

Mum grabs my arm.

‘I don’t want to hear that, young lady,’ says Boyd. ‘I want to hear that you’re very sorry and that you’ll never do it again. Do you understand? If you want me to have a chat with my senior and deal leniently with you because this is a first offence,’ he sizes me up squarely, ‘you’d better be smartening up your attitude.’

I feel my bravado draining like the colour from my mother’s face and start to cry.

‘So let me ask you again,’ says Boyd with mock patience. ‘Have you done the wrong thing?’

‘Yes.’

‘That’s right.’

Mum’s voice is tight with tears. ‘Can I take her home?’

‘Not yet,’ he says.

As we leave the interview room, other cops are manhandling a bunch of drunk boys, handcuffed, struggling and protesting loudly.

When they see us, one yells, ‘They fucken arrested us for no reason.’

Boyd ushers us out to a couple of benches in the dingy foyer where we meet up with Keek and his dad. Keek puts his hood up.

His dad flicks it down. ‘Stand up straight,’ he says.

‘It’s not his fault,’ I say.

There’s an uproar behind the darkened window: boys shouting, cops talking and phones ringing. After a while it quietens down, with only occasional yells of complaint from the boys, and laughter from the cops.

I lean on Mum, reading over her shoulder while she flicks through Blue Light, the police magazine. It’s trying hard to advertise their community spirit – every cop in it is a young person’s best friend. ‘Hmmm,’ she says and tosses it down. A minute later she picks it up again. It’s the only magazine available.

Mr McKenzie wanders around, reading and rereading the community service posters on the walls. Keek jiggles his knee, stares at the floor and doesn’t say a thing. The only bearable moment is when Mum lets loose a small but audible fart and we laugh.

‘Just when I thought things couldn’t get worse,’ she says.

It’s hours before Boyd appears again at the counter. ‘You’ve been damn lucky tonight; we’re going to let you go with a warning. Both of you. And we’re not going to see you again, are we, Clover?’ He clicks the end of his pen. ‘Are we?’

‘No,’ I say.

‘And Philip,’ Boyd shifts his attention, leaning in to point the finger. ‘I don’t want to see you in here again either, do you understand? You’re not helping Clover by encouraging her to break the law.’ He glances at our parents. ‘Take a seat, there’s paperwork to sort out.’

Another hour later, they finally let us leave. In the back of the car on the way home, I flop over and rest my head on Keek’s lap, watching street lights out the window flicker by. He doesn’t shove me off.

‘Thanks for driving, Dave,’ Mum says.

Mr McKenzie taps his thumbs against the steering wheel. ‘I think we’re lucky they brought in that bunch of drunken louts.’

‘Poor kids,’ Mum murmurs.

A mobile phone buzzes. Mr McKenzie throws it over the back to Keek. ‘Tell her we’re on the way.’

Keek answers and between bouts of silence, says ‘yes’ and ‘no’ and ‘sorry’ and ‘I promise’. He also strokes my hair, which is nice.

It’s getting light by the time Mr McKenzie drops us off. Mum leans in the driver’s window and kisses his cheek. ‘Thank you, David.’ She blows a kiss to Keek, who gets in the front. ‘And thank you Kee— Philip. I know you were trying to look after her. I’m so relieved it wasn’t anything worse than a warning.’

Keek mumbles, ‘Thanks,’ then looks up at me, standing by the passenger window. ‘Sorry, Clover.’

‘No, I’m sorry.’

Keek’s dad says, ‘Spare me,’ and drives away.

‘Mr McKenzie hates me.’

Mrs T appears in her fuzzy purple dressing-gown and Snoopy slippers. ‘Tsk. You know how scary it is to get a call from the police in the middle of the night? Your poor mother, she thought for a moment you were dead. Do you know how long such a moment can be?’ Then she hugs me, hard.

‘See, Mum, it could’ve been worse, at least I’m not dead,’ I squeeze out. ‘But I might be in a minute, Yiayia.’

I feel her ‘tsk tsk’ run through my body. ‘Clover, it’s no good, sneaking off in the midnight. Anything could happen to you!’

She lets go, but Mum takes my chin in her palm and meets my eyes. ‘No more graffiti.’

Two hours sleep is not enough. I can’t bear the thought of going to school. When Mum finally forces me out of bed, I slump at the kitchen table. ‘I’m not going.’

Mum reties the cord of her dressing-gown as if she’s strangling something. ‘You bloody are.’

‘You can’t make me.’

Something flips in Mum’s head and she tries to wrestle me into the bathroom. We struggle in the hallway for a minute before she lets go and shoves me. ‘Get ready for school.’

‘No.’

She screams, ‘Go to school!’ red-faced and strange, like some other person’s mother. I run into my room, slam the door and won’t let her in. With my shoulder to the door, it takes all my storming strength to keep her out.

Finally, she stops yelling, says, ‘Oh, fuck this,’ and there’s silence.

When I dare to come out to investigate, she’s gone to work. When she gets home, she won’t speak to me even though I’ve done the dishes without even being asked. She shuffles off to an early night as though she’s a thousand years old.

Two days of silent treatment and the fact that it’s nearly the weekend anyway forces me back to school. Thanks to Constable Ramidge’s son, Martin, who’s a year below me, everybody knows. Keek points him out as one of the ‘art fag’ crew. So much for him being my ‘fan’. But I am the tiniest bit cheered by the fact that Ramidge’s precious little boy is a rampant station-rat graffer called Catfood.

Cho bails me up in the corridor. ‘Why don’t you just leave Keek alone?’

‘Keek makes his own decisions.’ I’ve never punched anyone, but I’m wondering right now what it would be like. ‘Tell him off, if you’ve got a problem.’

‘He feels sorry for you . . .’

I’m rescued by Sutcliff, who orders me to follow her to the principal’s office.

‘You’ve tarnished the good name of Fernwood Secondary College,’ Berty tells me.

As if I care.

The Herbs, on the other hand, are so excited about me and Keek getting arrested that Rosemary Daniels decides to throw a party.

‘I knew it was you,’ she says. ‘And I think you’re cool.’

I endure a lengthy Saturday afternoon lecture from Aunty Jean along the lines of, ‘Your mother has sacrificed her whole life for you, Clover. She doesn’t need this crap.’ She grabs me for a rough hug. ‘Come on, it’s all too horrible, let’s go to the movies.’

We invite Keek, but he’s not allowed.

When we get back, Yiayia is huddled with my mother over cups of comforting tea. I feel instantly guilty. ‘What’s happened?’ I search around in panic for the dog, but Lucille’s under the table at Mum’s feet, as usual. She wags her tail and comes out to nose me for a pat.

Mum offers me a small, worn-out reassuring smile, but her voice is flat. ‘Dave rang. The creek—’ She stops, to swallow her tears. ‘Our appeal’s been rejected. Construction starts as scheduled, on Monday.’ She pushes the Fernwood Mail across the table. ‘And Jeff’s immortalised your shenanigans in a charming little piece reporting the decision.’

We can’t see what’s goin

g on at the roadworks from the fence at the bottom of the reserve, but the sound is unendurable. It’s a particular agony, the creak and crash of a felled tree; discernible even over the roar of the chainsaw and rumble of machinery.

‘I’ll catch up with you later,’ I tell Keek when Cho and the others ride up, and wander off home.

I’ve been driven along roads like the one they’re building behind the reserve; where the remaining treetops peep over the noise barriers. Roads that aren’t essential – roads that only get us to where we can already go, faster. Scuffing along the footpath, I wonder about all the concrete and tar we’ve poured over everything. It’s a crime we’ve committed against nature, but nobody thinks of suburbs and cities as ‘criminal damage’. But when I put paint on that concrete, those buildings, that’s exactly what they call it. Shouldn’t we be planting trees, not chopping them down? Shouldn’t we be nurturing the green belts that still exist? And not just in Australia, but everywhere. I don’t want the earth to shrivel like a dried apricot, or sink under salt water.

‘Hello, Clover.’

Her voice makes me jump.

‘Hello, Mrs Sutcliff.’

It’s bizarre seeing her out of school. She seems small and scruffy, her clothes have the familiar grubby dishevelment of a woman who’s been gardening.

‘Just out to get milk,’ she says, lifting her empty green shopping bag as if she has to explain. She peers at me. ‘Are you crying?’

‘I’m fine.’ I pathetically sniffle up my sleeve. ‘Thanks.’

‘Righto.’ She strides off and pauses to turn back. ‘Laila Yamouni spoke highly of you in the staffroom. I was very happy to hear it.’ She spears me with one of her sharp looks. ‘I always knew you had terrific potential.’

I sit on the nature strip to watch her disappear around the corner into Main Street.

Keek rocks up. ‘What are you doing?’ he says.

‘I think I’ve just had a hallucination.’

He steps off his bike and crouches, suddenly pale and worried. ‘Serious?’

‘No.’

He sits next to me on the grass and looks so relieved, I have to wonder what the heck goes on in Keek’s house.

I thought the trouble with the cops was all over, but at half-past-seven on Sunday morning, John Archer turns up on our doorstep to complain to my mother and give me a serve for the piece I stencilled on the footpath outside his pharmacy. He waggles a rolled-up copy of the Fernwood Mail. ‘It doesn’t take a genius to figure out who’s the culprit.’ He seems disappointed they haven’t locked me up and insists we go with him to ‘examine the damage’. Mum rolls her eyes behind his back, but says, ‘Come on, Clover, get in the car.’

The shop has been crappily tagged by ‘nobitz’ and ‘gutz’. I have to agree, it’s awful. With a stab, I see nobitz has also tagged my footpath piece – a direct insult to the quality of my work. Or maybe he’s just a dickhead. I can’t look at the pharmacist: how I feel about nobitz must be how he feels about me.

‘I’m sorry,’ I manage, and turn to Mum. ‘I only chose this spot because you can see it from both ends of the street.’

Archer crosses his arms. ‘Well, what are you going to do about it?’

‘Clover and I could repaint the outside of your shop?’ my mother suggests weakly.

‘I’m getting it done professionally,’ he says. ‘I’m sorry, Penny, but I’ll be forwarding the bill to you.’ He doesn’t look sorry.

Mum says, ‘Yes, of course,’ with that embarrassed, pinched face she gets when the EFTPOS machine comes up ‘insufficient funds’. It’s unbearable.

‘I understand why you hate tags,’ I blurt. ‘And I’m sorry they messed up your shop. But I didn’t touch your shop. And anyway, those kids just want to be heard too, you know. They want someone to know they exist. And what about what’s happening to the creek? And all these ugly buildings. Aren’t they acts of vandalism?’

Archer dismisses me with the shake of his head. ‘I don’t know what’s happened to young people,’ he says to my mother.

‘They woke up,’ she flashes at him. ‘Send me your bill, John, if it will make you feel better about yourself,’ and she stalks away.

I practically have to run to catch up with her.

But when we get home, she goes into my room with a rubbish bag and confiscates my paint. ‘Not my Monstercolours!’ I beg and cry, but she’s made of stone. Then she crawls into bed with Lucille, a pen and a writing pad, and won’t come out.

My beautiful tins! I throw myself on my own bed and ache with loss. After a few hours, I recover enough to complain about being starving.

‘What am I supposed to eat?’

‘There’s eggs. You can make me some too, while you’re at it.’

‘What?’

‘And feed the dog.’

‘It’s tonight,’ I tell Keek on my front porch, ready to head to the bowl. ‘The party. Rosemary’s parents have gone to Tasmania for the weekend.’

‘I’m not going.’

‘Why not?’

‘Mum won’t let me. She’s hardly stopped crying since the cops called in the middle of the night. I’m only here because she’s asleep and doesn’t know.’

‘But it’s for you.’

Keek’s face floods red and he shouts, ‘No it’s not, Clover. It’s for you.’

I shout back. ‘It’s for us.’

‘It’s for you.’

And he rides off, without me.

‘At least leave me a smoke,’ I yell.

‘Get your own.’ And he’s gone.

I stand in Mum’s bedroom doorway. She’s propped up in bed reading, even though it’s almost eleven o’clock. Lucille sits up and wags her tail. I pat her bony old head, her once-black face almost completely white, her eyes cloudy, and smell the familiar doggy smell of her.

‘You stink,’ I say, and kiss her nose. ‘Aren’t you getting up?’

‘It’s Saturday.’

‘It’s nearly lunchtime.’

She twitches an indifferent shoulder and turns her attention back to her book. Lucille treads a few circles, collapses into comfort and lets out a big sigh.

‘Everybody’s mad with me.’

‘You mean Keek?’

‘You heard?’

‘I heard the shouting. Sounds like you’d better get yourself a job.’

‘What do you mean?’

‘To pay for your cigarettes.’

Mum looks at me. I look away. There’s no use denying it. She goes back to reading, but disappointment wafts off her like yesterday’s garlic.

‘Rosemary Daniels has invited me for a sleepover.’

‘I don’t want to drive anywhere today, Clover.’

‘I’ll walk.’

‘Is her mother going to be home?’

‘Yeah. It’s a sleepover.’

‘Okay then.’

‘Thanks.’ I sit next to her and give her a hug. She hugs me back, but it’s lukewarm and when I turn at the door to say, ‘I’ll come and say goodbye before I head off,’ she has already rolled over and is staring out the window.

‘Yes. Please do.’ She doesn’t even look around, let alone offer to get up and help me pack a bag, or change her mind about driving.

Her purse is on the kitchen bench where she always leaves it, near her car keys. Checking over my shoulder, I open it. A ten and a twenty dollar note stare back at me.

‘You sure you don’t want to drive me?’ I wheedle when I kiss her goodbye.

‘Quite sure,’ she says. ‘Now I’m trusting you, so be good.’

‘I am good, Mum,’ I lie.

‘Do you know Robbo’s nearly eighteen?’ Thyme asks me.

On Rosemary’s instructions, we’re moving the couch to make room for dancing. ‘He had to stay down a year in primary school because he had bad appendix-itis and got really sick and spent nearly the whole year home from school.’

‘Appendicitis,’ I correct her.

‘Yeah,’ she sa

ys. ‘It’s when your appendix gets swollen, or something.’

‘How’s it going for you two?’

‘Me and Robbo?’ Thyme looks mildly shocked, as if she’d never considered them a couple. ‘Nah, I’m hooking up with Jason Eldrich tonight if it kills me.’

‘Doesn’t Parsley like Jase? They’ve been hanging out at school.’

Thyme stops like she’s been donged on the head. ‘Parsley?’

‘What?’

‘You said parsley.’

‘Parsley? No. Natalie.’

Thyme gives me a confused, suspicious look then jiggles her shoulders. ‘She had her chance. Guys like Jason don’t want frigit girls.’

‘Isn’t it frigid?’

‘That’s what I said.’

‘Maybe Jason’s not like that? Maybe he likes Natalie for who she is?’

‘Don’t be a dickhead, Clover. Pete Tsaparis already told me that Jason told all the guys that Natalie’s frigit. So—’

‘So—?’

‘So, that’s why I’m hooking up with him tonight.’

‘What about Natalie?’

She tosses her hair. ‘Like I said, she had her chance.

Anyway, what do you care?’

‘I don’t know.’ I tidy couch cushions like a grandma. ‘Won’t she . . . I don’t know. Be upset?’

‘Life’s tough, she’ll have to get used to it.’ Thyme plucks up the cushions and tosses them into the corner. ‘Maybe the next time she’s got the guy she likes where she wants him, she’ll know what to do to keep him.’

‘It didn’t make any difference with you and Robbo.’

Thyme looks hurt. ‘Jeez, you can be a bitch,’ she says.

I’m relieved when the other two Herbs roll in.

Watching Thyme act like Parsley’s best friend, I decide the best thing for me to do is to stay as far away from Rob Marcello and his footy mates as possible.

But I don’t feel like that when he plonks down his little esky and sits next to me on the back porch where I’ve gone to smoke as soon as everybody starts arriving.

‘Do you want a beer?’ he asks me.

‘No thanks. I hate beer.’ Aunty Jean’s favourite drink. Yuck.

‘Cruiser then? Sherbet one?’

Cracked

Cracked